Sunday, January 17, 2010

What is my Higher Power?

It would be very complex to explain exactly what brought me away from the church. It's fair to say that it wasn't any one event in particular, and this seems to be true of most people that I have spoken to who left the churches in which they were brought up. My drift began in my early 20s, when certain dissonances between the teachings of the church and what I believed intrinsically became too loud to ignore any further. There were certainly times in my church-going years that I was hurt by "The Church", mostly by attitudes held by those in authority that I thought directly contradicted the church's teachings. I understood that the church is composed of people, and that anytime groups of people gather, difficult politics are inevitable. But over time I came to believe that the main concept underlying all church teachings (and I'm not talking about Episcopalian ones specifically, but Christianity in general) was judgement. People were implicitly, sometimes explicitly, encouraged to judge others, and mistreatment follows. After a time I could no longer participate in something I felt so conflicted about.

It was a few more years before I was able to admit to myself that I didn't actually believe in the God of my childhood. I felt tremendous guilt over my lack of "faith". It wasn't until I finally realized that the only thing keeping me from embracing what I truly did believe was the guilt I felt over abandoning the faith of my parents that I was able to understand what I really believed in. What I really believed in was this: This life is what we have, and when we die that is it. It is up to us to be good to one another, to make life better for all people. We have a moral responsibility to do our part to minimize or eliminate suffering of others whenever we had the ability to do so. Hell is not a place, but rather it is something we create ourselves on earth. Same with heaven. There is a basic goodness to the universe, and we are all born with it.

When I first came to 12 Step recovery last year, I learned that it was a "spiritual program." I was going to have to have a Higher Power in order to work the steps. This filled me with fear and anger. I had only recently come to realize that I was an ignostic: basically, not one who believes there is no God, but one who thinks it's the wrong question to ask. (This is also known as theological noncognitivism.) At the time, I thought I would have to abandon this deeply rooted belief of mine if I was to go any further in 12 step recovery.

Fortunately, I was reading a book by Kevin Griffin called One Breath At A Time, about Buddhism and the 12 steps. It helped me to understand that "God" truly is a concept that is left to the individual, and that my concept of a Higher Power did not need to be Judeo-Christian. The book is specifically about how to incorporate one's Buddhist beliefs into 12 step recovery (wonderfully written and highly recommended for this), but I think even a non-Buddhist in this situation could gain a lot of understanding just about the concept of Higher Power.

There are those people who use the group as their Higher Power, or the doorknob of the room they meet in. I think the doorknob is a cop-out personally, but that isn't for me to define for someone else. The idea, according to the program literature, is simply that you yourself are not your own Higher Power, that you believe in some power greater than yourself, whatever it may be. I can see how the group can be this for someone resistant to any other idea of a HP.

Ultimately, here is what I have come to understand as my Higher Power. I think there is a Power of goodness that is the Universe. I think all beings are interconnected by this basic goodness. It is not a personal God for me: I don't think there is a celestial, mystical or supernatural being who intercedes on my behalf and has a consciousness. Buddha isn't my HP, as he isn't a God. But the Buddhas that have existed, as well as the Bodhisattavas, point the way to the basic goodness and order of the universe. Can an impersonal HP "restore me to sanity"? Yes. Understanding this goodness of the universe, and freeing myself from delusion that separates me from that awakening, is certainly a restoration to sanity. Understanding the dharma, learning the origins of suffering, and discerning the Right Path, all lead to a Higher Power. And it certainly is not me.

Here is what Rev. Tanaka has to say about Buddhists and God. He seems to feel that Buddhists hold an ignostic view of God:

=====================================

Do Buddhists believe in God?

Before I can answer that question, I must ask, what is meant by “God”? People have many ideas about who or what God is. Until I understand this, it is hard for me to answer. If God is defined primarily as cosmic compassion and wisdom, then some Buddhists (particularly Mahayana Buddhists—see page 47) may be inclined to say they believe in “God.” But that will be personal decision of a modern Buddhist. As for me, I would exercise a great deal of caution, making sure that “God” is clearly defined and acceptable to me as a Buddhist. On the other hand, if God is a supreme personal being who created the universe, lives in heaven, watches over me, and knows my thoughts and actions, then Buddhists clearly do not believe in God.

Then, Buddhists do not believe in anything supernatural?

No, that is not exactly what I meant to say. Instead of a personal divine creator, Buddhists have always spoken of an enlightened reality called “Dharma.”

This Dharma as “reality” is the source for the Dharma as the “teaching” we talked about before (see page 9). The English translation of this Dharma (dharmakaya, dharmata, dharmadhatu, etc.) includes Law, Logos, Suchness, Truth, and Reality. In modern everyday language, this Dharma can be described as Life, Universe, Cosmic Compassion, Life-giving Force, or Energy. I like the word “Oneness” because it reminds us that the enlightened reality (Dharma) is not separate from us. We are actually one with Dharma. It’s right under our feet, but we don’t know it.

Do Buddhists Pray?

I read the following section this morning about prayer and Buddhists:

=======================================

Do you pray?

Yes we do, but not to the same extent or in the same manner as in Western traditions. This is partly because we emphasize meditation and reflection more than prayer. The other reason, of course, lies in the absence of a supreme divine being to whom one can pray.

I understand there are many kinds of prayer in Christianity, including thanksgiving, blessing, intercession and invocation. In the Buddhist tradition,

too, gratitude (similar to Christian “thanksgiving”) plays a vital role in the thoughts and actions of Buddhists. This is especially true among the Jodo-Shinshu Buddhists for whom gratitude constitutes the primary motivation for much of their religious and worldly actions. Similarly, Buddhists seek blessings for the happiness of all beings. “May all beings be happy” is the constant refrain in the Loving Kindness Sutta (or Sutra) that is most frequently chanted as a blessing by Buddhists of Southeast Asian background. Also, the Buddhists do “intercede” on behalf of others when they hear about misfortunes of others such as an illness. Particularly the Buddhists of Southeast Asian background mindfully direct their thoughts to others. “May they get well; may they be happy.”

But our concern for them should not simply stop here. To pray is easy, but a true test of our concern for others lies in our deeds, such as visiting them at the hospital or assisting the family with the chores during trying times.================================

For many of us who are former theists, the word "prayer" has an unpleasant connotation. It seems this word can actually be expanded to more uses than just "Our Father". I've been trying to work on my aversion to the term "prayer" and references to "God" for some time, with minimal success. I can understand how the word can mean more than the narrow meaning it held in church, but my gut reaction is still aversion.

Many Buddhists prefer to think of these thoughts that Rev. Tanaka calls "prayer" as "meditation." Perhaps this is an Americanization, too. Many American Buddhists (perhaps most) are former church-goers, and left Christianity and/or theism for a reason. Perhaps the word "meditation" is a useful distance from the old connotation of the word "prayer".

[I should note here that "meditation" and "prayer" are not direct synonyms. There are many kinds of meditation, and some of them resemble prayer, while others are exercises in no-thought, so that the directed, specific ideas of prayer would not apply.]

But for me, in my 12 step work, the word comes up a lot, and many people talk a lot about prayer. I really can't avoid it. The word bothers me, but I have to release my aversion to it. I'm not praying to a personal Higher Power, but I do ask for happiness and peace for myself and others. I do give thanks for life and blessings. I do seek greater meaning in life, and try to understand the right path in a given situation. These things are prayer, or meditation. Take your pick.

Unfortunately, the word "prayer" has also been politicized in the United States, as so many other spiritual concepts have been politicized here. People talk about prayer in schools, and those who do are understood to be a certain "brand" of Christian, often those who believe that we live in a Christian nation, "one nation under God", and are intolerant of other expressions of faith or non-belief.

One thing I find difficult at meetings is when the meeting is closed with traditional Christian prayers, like the Lord's Prayer. The words of the Lord's Prayer, while beautiful, speak of a personal God in heaven, who does certain things for those praying. I understand that it is very meaningful for Christians; I was one, once. But to me, its use in 12 step meetings goes against the concept that "God" is defined by the individual, the "God of our understanding." The "God" spoken of in the Lord's Prayer does not resemble the "God of my understanding" at all. Sometimes I don't say it at all. Sometimes I am too weary of doing all the "translation" in my head to make the words coming out of my mouth feel authentic to my own belief. And I admit that I become resentful of the group's forcing their own God of their understanding onto me then.

Yet, I have no problem with the Serenity Prayer. It is a simple and powerful concept, and to me has little to do with defining God or asking a god to do something for me. I say it often to myself in difficult situations, and use it like meditation. Opening and closing a meeting with the Serenity Prayer offers a kind of peace and balance, and helps me achieve mindfulness. It also helps to solidify what I think is an important focus for every 12 step meeting: understanding that we are not personally in control of most things, especially addiction.

I think it is important to make peace with prayer. Prayer, or meditation (if you prefer), is a powerful way to get your mind off yourself and to think more expansively. Being able to pray for others--say, stopping to pray for a person that you resent--can help you achieve mindfulness. It is easier to think of ourselves and others with kindness and compassion when we can get out of our ego and think in the way we call prayer.

I identify as an ignostic humanist these days, but consider myself to be spiritual. I don't appreciate the fact that prayer has been co-opted by those who would consider my spiritual practices to be amoral or immoral or pagan. I do have a Higher Power, which I will talk about in my next post. But making peace with prayer is important for recovery, and I am working on this in my own life and path.

Monday, January 11, 2010

The Monster walks among us

This time, I made a mental note of the times that I thought I smelled alcohol on his breath, the times I thought he might be lying to me, the peculiar behavior that was different in a familiar way. I confronted him about it a few times, but mostly just paid attention. I would like to say that this was accompanied by a great deal of serenity and working my program, instead of the craziness that I did feel. I never knew what to expect when I came home from work. I found a total of 4 bottles of liquor (mostly or completely empty) in the last 5 months, and I think a great many more were disposed of before I could see them.

I am terribly sad about this. But, we were finally able to have an honest, if painful, conversation about it all last week. My husband is trying sobriety again. I hope he can make it work. I know that most seasoned AA people, as well as those who work in the field of addiction, say that relapse is an unfortunate eventuality for most recovering alcoholics, and that it doesn't mean that all is lost. Each relapse can be a learning opportunity for the alcoholic who truly desires recovery and sobriety. I hope that is the case for my husband.

I've learned some more things about myself in the intervening time, and some things have changed in me. I know how it feels to be lied to, and to know deep down that I'm being lied to even if I'm not consciously certain of it. I know the pain of losing my trust in the person I love most. And I know that I cannot be one of those old women in Al-Anon who works her program and lives serenely and consciously with active addiction for years. I can't control anything about my partner's sobriety, but I can make my own choice about what I am willing to live with.

I was very, very close to leaving this marriage last week, when it seemed that my husband had no desire to be sober and no desire to take any care of himself. He has been getting no exercise, has been vomiting up blood and living with terrible insomnia for weeks. He has profound depression yet has refused to treat it. He seemed to be killing himself slowly, right before my eyes. I couldn't stay to watch that, and felt he was not living up to his end of the bargain in this marriage by not choosing to care for himself.

I hope that his rededication to his program and to his sobriety is for himself, and not simply an attempt to keep me here. It's another thing I have no control over. Only time will tell. It is a little bit easier to give all of this another chance, now that I have a better idea of what my limits and options are. But I am weary, and sad and uncertain.

Addiction and The Wheel of Life

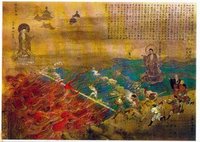

Yesterday's service at our Buddhist temple featured a Dharma talk by our minister's assistant about samsara, the Wheel of Life, and the Three Poisons. She brought in a visual aid, a large mandala depicting the Wheel of Life, very much like the image I found and posted here. The wheel is held up by the god of death, Yama (considered a protector of Buddhism in Tibet.) She described him holding a mirror to those of us locked in samsara, or the cycle of birth and death marked by suffering. The upper part of the picture shows where the bodhisattvas are, those who have escaped samsara and are pledged to help everyone else escape. The center shows the Three Poisons, which are desire or attachment, aversion or hatred, and delusion or ignorance. These are the causes of our suffering.

Yesterday's service at our Buddhist temple featured a Dharma talk by our minister's assistant about samsara, the Wheel of Life, and the Three Poisons. She brought in a visual aid, a large mandala depicting the Wheel of Life, very much like the image I found and posted here. The wheel is held up by the god of death, Yama (considered a protector of Buddhism in Tibet.) She described him holding a mirror to those of us locked in samsara, or the cycle of birth and death marked by suffering. The upper part of the picture shows where the bodhisattvas are, those who have escaped samsara and are pledged to help everyone else escape. The center shows the Three Poisons, which are desire or attachment, aversion or hatred, and delusion or ignorance. These are the causes of our suffering.These Three Poisons are the heart of Al-Anon and S-Anon's concepts of how we are affected by another person's addiction.

- Desire, or attatchment, is known in the program as our fixation on the actions of others, and our desire to control them in order to control our own fear. We are attached to the idea of how we want the addict in our lives to act, and how we want to act ourselves.

- Aversion, or hatred, is something easy for anyone who has lived with active addiction to understand. We may not have aversion or hatred for the addict (and if we do, we learn in the program to separate the addiction from the addict, and to see addicts "as sick people, not bad people.") But we do have aversion/hatred for the disease, and for the unmanageability of our own lives as a result. We may have aversion or hatred for ourselves even, as a result of trying to live with addiction. This also speaks to the resentment that we have to deal with. (I think SA and AA deal with the concept of resentment much better than the Anon meetings I go to do.)

- Delusion, or ignorance, is our denial. Our denial has certainly caused suffering, which we term unmanageability. One of the first things we have to learn in the program is how to see life as it really is, not how we have struggled to believe it is. Interestingly, it is also one of the main goals of Buddhism, to see life as it really is and to be "free from all delusion."

In between our birth and our death, we suffer, and this is inevitable as long as we are locked within the cycle. We suffer because we cannot overcome our desire, hatred, and delusion.

I struggle every day with accepting the reality of addiction in my life. I don't have much difficulty separating my husband from his addiction, but I do struggle with seeing the behavior caused by addiction as something he does despite a desire to do otherwise. I love my husband, and I am proud of the work he has done in the last year to improve his life and his attempts to behave differently than his addictions seem to dictate. But I still cling to the notion that I didn't ask for addiction to be a part of my life, and I am angry at the number of ways I am forced to live with it. It may be true that I didn't ask for this, that it isn't fair that we have to deal with all of the negative consequences of addiction and its associated behavior. But it is still the reality of this life. Wishing for things to be different doesn't make it so.

I struggle every day with accepting the reality of addiction in my life. I don't have much difficulty separating my husband from his addiction, but I do struggle with seeing the behavior caused by addiction as something he does despite a desire to do otherwise. I love my husband, and I am proud of the work he has done in the last year to improve his life and his attempts to behave differently than his addictions seem to dictate. But I still cling to the notion that I didn't ask for addiction to be a part of my life, and I am angry at the number of ways I am forced to live with it. It may be true that I didn't ask for this, that it isn't fair that we have to deal with all of the negative consequences of addiction and its associated behavior. But it is still the reality of this life. Wishing for things to be different doesn't make it so.

While I notice suffering in the moment, it helps to understand that this too shall pass. If I am able to learn to stop clinging to things, good and bad things, if I can see things as they really are and not how I want them to be, if I can free myself from hatred, then I can stop suffering. It doesn't matter what others are doing all around me, and this is the essence of Al-Anon and S-Anon as well as Buddhism. I don't know if it is harder for me than other people. Probably not. But it feels so hard to not desire things to be a certain way. I am still working on it, and still learning.